State level society and the Book of Mormon

|

| De Soto discovers the Mississippi |

The basic thesis of the article follows this logic:

1. Societies progress over time, starting with a tribal society and progressing into a state-level society.

2. These levels of society can be demonstrated by archaeological evidence.

3. The Book of Mormon describes state-level society, with some regression into tribal society described in 3 Nephi.

4. Archaeological evidence shows tribal societies in North America and state-level societies in Mesoamerica.

5. Therefore, the Book of Mormon must have taken place in Mesoamerica.

It seems to me the article misreads Book of Mormon history and also ignores archaeological evidence from North America that contradicts its conclusion.

1. The Book of Mormon describes mostly tribal or chiefdom societies, except for an interlude of a Nephite state-level society from about 84 B.C. to about 30 A.D. This state-level society was constantly weakened by wars and iniquity. The Lamanite adversaries (much larger tribal or chiefdom societies) were obsessed with destroying Nephite society and accomplished their goals in around 385 A.D. Consequently, according to the text, we should be looking for an area where tribal societies dominated, with little if any evidence of the state-level society surviving the wars and catastrophes.

2. Archaeology shows monumental architecture in North America–sophisticated and massive mound structures–that survived from the Nephite era to the present day and match the descriptions in the text. It doesn’t show evidence of writing, abstract thinking (apart from geometry and astronomy), sophisticated art, etc., all of which would be targets of Lamanite destruction.

3. Archaeology also shows extensive stonework, temples, and engravings on monuments in Mesoamerica–indicia of widespread state-level societies–that are never mentioned in the text.

As a result, consideration of tribal, chiefdom, and state-level societies helps to understand how the North American setting fits the text.

______________

Here are some of my thoughts that I submit for consideration. In my view, the state vs tribal analysis supports the North American setting.

The basic premise of the article is that there is archaeological evidence of state-level society in Mesoamerica but no evidence of state-level society in North America.

The article cites a paper by David Ronfeldt titled “In Search of How Societies Work.” That paper is based on a theory of social evolution. “This paper is the latest in a string of efforts to develop a theoretical framework about social evolution, based on how people and their societies use four major forms of organization: tribes, hierarchical institutions, markets, and networks.”

The article includes two lists, one of characteristics of state-level society, the other of tribal society, each accompanied by scriptural citations to the Book of Mormon. There is a photo of Hopewell artifacts, which the article claims was “diagnostically characteristic of tribalism.” This is followed by a photo of Mayan hieroglyphs from Palenque, accompanied by the observation that “classic lowland Maya society achieved state level.”

The article concludes, “State level societies leave unmistakable traces that scientists recognize. No North American culture known to science achieved state level society during Book of Mormon times. Several Mesoamerican cultures achieved state level societies during Book of Mormon times. John L. Sorenson succinctly summed up the situation: “Only one area in ancient America had cities and books: Mesoamerica.” Mormon’s Codex p. 21.”

Before introducing the list of tribal characteristics, all drawn from 3 Nephi, the article observes that “The Book of Mormon unequivocally describes state level society, as well as the precise moment when complex Nephite government degenerated into tribalism 3 Nephi 7:2-4.”

The Ronfeldt article discusses such regression.

“THE ULTIMATE FALLBACK FORM

“The tribal form remains not only an essential basis for the functioning of complex

societies but also the natural fallback option if the other TIMN forms falter or fail. Then

it again becomes the primal form of organization and behavior. People revert to it as a

sensible way to regroup and protect themselves under dire conditions—perhaps to start

rebuilding a society, or just to regress into a violent, recidivist rage against outsiders.”

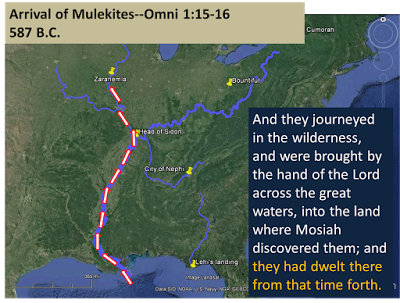

Book of Mormon history starts with a tribe (Lehi’s family) leaving a state (Jerusalem) that faced imminent destruction. Once in the Promised Land, Lehi’s tribe divides into smaller tribes. The text implies that indigenous peoples are incorporated into Nephite and Lamanite society; at no time do the Nephites adopt an indigenous culture (but the Lamanites may have). Instead, the Nephites observe the law of Moses strictly. Nephite society becomes more sophisticated, while Lamanite society remains more primitive or tribal.

The article observes that “One word commonly associated with tribal societies is “tradition.” One word commonly associated with state level societies is “command.” Nephite writers often associated Lamanites with traditions as in Mosiah 1:5, Alma 9:16, and Helaman 15:4. Nephite writers often associated Nephites and deity with commands as in Alma 5:61, Helaman 14:9 and 3 Nephi 23:13. Another word commonly associated with tribal societies is “identity.” A word commonly associated with state level societies is ‘institution.'”

This all makes sense. Essentially, Lamanites were tribal; Nephites had a state-level society (for about 150 years, albeit severely disrupted by warfare and internal disruption, until the destruction in 3 Nephi; it’s not clear what kind of society they had after that).

The Book of Mormon text emphasizes throughout that the Lamanites were far larger in population and, ultimately, destroyed the Nephite society. (Nephite society was also smaller than the larger society of Zarahemla, which exhibited none of the characteristics of state-level society; i.e., no writing, no cities, no organized religion, etc.) Consequently, throughout the Book of Mormon, tribal societies dominated in terms of population and territory. To find the setting for the Book of Mormon, we need to find a place where there is relatively little evidence of state-level society. Plus, any evidence of a state-level society would have to survive 1) the massive destruction described in 3 Nephi and 2) the determined and aggressive effort by the Lamanites to destroy any vestiges of Nephite society, including written records.

That’s exactly what we find in North America. And, as the article points out, it’s exactly what we don’t find in Mesoamerica.

___________________________

The article itemizes these criteria for state-level society:

Anthropologists use criteria to distinguish tribal societies from more sophisticated civilizations that reach state level. These criteria include:

- Social stratification. Tribal societies develop a chiefly elite who outrank commoners. State level societies have complex social class hierarchies, each with different access to resources. Alma 51:8, 3 Nephi 6:12.

- Dense populations. Tribal societies settle extensively across their ecosystems. State level societies support intensive populations. Omni 1:17, Ether 7:11.

- Urbanization. Tribal societies build hamlets and villages with occasional towns at particularly favorable sites such as the confluence of two rivers. State level societies build large, well-organized cities and city states. Mosiah 27:6, Helaman 7:22.

- Food surpluses. Tribal societies subsist on hunting, agriculture, and extractive industries. State level societies produce surplus food that gets re-distributed to urban centers. Alma 1:29, Helaman 6:12.

- Labor specialization. People in tribal societies tend to work in homogeneous occupations closely tied to nature. State level societies produce artisans Mosiah 11:10, lawyers Alma 10:15, merchants 3 Nephi 6:11, etc. who work in a wide variety of vocations.

- Centralized government. Tribal societies organize along kinship lines. State level societies develop formal ruling institutions Alma 11:2 where shared ideologies Mosiah 29:39 allow elites to control power Mosiah 29:2.

- Controlled trade. Tribal societies engage in long-distance trade of exotic goods. In state level societies, elites control trading networks to maximize their wealth Ether 10:22.

- Public works. Tribal societies erect stones and heap up dirt. State level societies build monumental architecture such as palaces Mosiah 11:9, pyramids Mosiah 11:12, temples Alma 16:3, roads 3 Nephi 6:8, markets Helaman 7:10, etc.

- Written records. Tribal societies communicate verbally and with ideograms. State level societies use writing systems Mosiah 28:11, develop widespread literacy Alma 46:19, and maintain record archives Jarom 1:14, Helaman 3:15.

- Symbolic art. Tribal societies produce naturalistic art. State level societies portray symbol complexes representing abstract or theological ideas 1 Nephi 11:7-11, Alma 32:28.

- Intellectual disciplines. Tribal societies orally transmit traditional wisdom. State level societies develop organized branches of knowledge such as biology Alma 46:40, physics Helaman 12:15, mathematics Alma 11:5-19, etc.

- Standing armies. Tribal societies muster attackers or defenders based on perceived vulnerabilities or threats. State level societies maintain a professional military apparatus Alma 2:13, Alma 62:43.

- Organized religion. Tribal societies have shamans, councils, and localized rituals. State level societies develop a priestly class overseeing religious institutions Mosiah 25:21-23, Alma 6:1.

I didn’t see a citation for these criteria, but the distinction between state-level and tribal societies is not binary. The sharp distinction implied by the article obscures the fluid reality of social development.

Ronfeldt notes an intermediate transitional stage of chiefdom. “Many anthropologists view the chiefdom as a distinct type of society that lies between the tribe and the early state. But in the TIMN framework, the chiefdom is a transition in which the tribal form is suffused and combined with the hierarchical form, yet the hierarchical form is still far from taking hold…. Chiefdoms could undertake activities that tribes could not, such as building public works and monuments, making larger weapon systems (e.g., long canoes), storing part of a harvest in a central granary, collecting tributes and taxes, organizing large ceremonies, arranging trade deals with outsiders, forming up for war, and making treaties. And as chiefdoms did so, the tribal propensity for egalitarian reciprocity gave way to a new

emphasis on inegalitarian redistribution; indeed, the shift from reciprocity to redistribution is a key theme in the literature on chiefdoms.”

Furthermore, Ronfeldt observes that “the most vigorous debates I have encountered concern the transition from tribes, to chiefdoms, to states. The major explanatory factors that scholars repeatedly posit for this transition are increases in population, in economic production, in local and long distance

trade, in warfare and conquest, and in social stratification. All these increases generate impulses and opportunities for central coordination and control, and thus for the emergence of specialized administrative and bureaucratic hierarchies—i.e., for the rise of the +I form.”

Chiefdom seems an apt description of Nephite society, although the Nephites used a system of elected judges instead of chiefs. “Secular and sacred roles also remained fused in this phase,” Ronfeldt explains. When Alma resigned the judgment seat (Alma 4:16-18), this may have marked a turn toward a state-level society. But it didn’t last long. Alma resigned about 84 BC. By 73 BC. Amalickiah sought to be king (or chief), with considerable support. The conflict between king-men and freemen reflects the difficult transition from chiefdom to state-level societies. The wars, the Gadiantons, and other problems caused continual turmoil. It wasn’t until around 30 B.C. that the people began to prosper, but the prosperity was short-lived.

I won’t take the time to go through each criteria, but one example shows how well the criteria match the text and the ancient North American cultures.

- Public works. Tribal societies erect stones and heap up dirt. State level societies build monumental architecture such as palaces Mosiah 11:9, pyramids Mosiah 11:12, temples Alma 16:3, roads 3 Nephi 6:8, markets Helaman 7:10, etc.

Let’s say tribal societies “erect stones and heap up dirt,” while state level societies “build monumental architecture.” Where do we find a society that erects stones? Not in North America–and not in the Book of Mormon. Mesoamerican societies are characterized by erected stones.

Where do we find societies that “heap up dirt?” In Alma 2:38, bones are “heaped up on the earth.” In Alma 16:11, “their dead bodies were heaped up upon the face of the earth and they were covered with a shallow covering.” In Alma 28:11, “the bodies of many thousands are moldering in heaps upon the face of the earth.” General Moroni caused that his armies “should commence in digging up heaps of earth round about all the cities.” All of these heaps are common in North America.

In addition, General Moroni’s army “had cast up dirt round about to shield them from the arrows and the stones of the Lamanites.” (Alma 49:2). “They cast up dirt out of the ditch against the breastwork of timbers.” (Alma 53:4). This is such an apt description of Hopewell fortifications that the Book of Mormon has been accused of relating commonly known aspects of moundbuilder culture.

What about monumental architecture?

“Monumental architecture, to archaeologists anyway, refers to large man-made structures of stone or earth. These generally are used as public buildings or spaces, such as pyramids, large tombs, large mounds (but not single burials), plazas, platform mounds, temples, standing stones, and the like. The defining characteristic of monumental architecture is typically its public nature–the fact that the structure or space was built by lots of people for lots of people to look at or share in the use of, whether the labor was coerced or consensual.”

The largest geometric earthwork complex in the world is in Newark, Ohio. “Enormous enclosures connected by walled roadways were spread across more than four square miles. This was the most spectacular of many such earthworks, concentrated along the tributaries of the Ohio River, marking the people’s beliefs, rituals, and sense of community.”

“In 1982, professors Ray Hively and Robert Horn of Earlham College in Indiana discovered that the Hopewell builders aligned these earthworks to the complicated cycle of risings and settings of the moon. They recovered a remarkable wealth of indigenous knowledge relating to geometry and astronomy encoded in the design of these earthworks. The Octagon Earthworks, in particular, are aligned to the four moonrises and four moonsets that mark the limits of a complicated 18.6-year-long cycle.”

By any definition, these earthworks are monumental in scale and sophistication.

The scriptural citations in the article regarding a state-level society are important. The palace referred to in Mosiah 11:9 was made of wood: “And he also built him a spacious palace, and a throne in the midst thereof, all of which was of fine wood and was ornamented with gold and silver and with precious things.” The Book of Mormon never describes the use of stone for constructing buildings. Stone was used as a weapon and, in one occasion, to build walls. Instead, people used wood for construction (and in a particular case, cement). To find a setting for the Book of Mormon, we need to look for a culture that used wood, not stone, for construction.

The pyramids referred to in Mosiah 11:12 don’t show up in my version of the text. That verse refers to a high tower built near the temple. My search engine doesn’t find the term “pyramid” anywhere in the text. Consequently, we would not expect to find pyramids in an area where the Book of Mormon took place.

Temples are mentioned in many place in the text. Alma 16:13 explains that temples, sanctuaries and synagogues were built after the manner of the Jews. The Jews never built pyramids.

Roads are a good indicator of advanced civilization. 3 Nephi 6:8 explains “And there were many highways cast up, and many roads made, which led from city to city, and from land to land, and from place to place.” How many of these highways survived the destruction is unclear. Samuel prophesied that “many highways shall be broken up, and many cities shall become desolate.” (Hel. 14:24). And, in fact, “the highways were broken up, and the level roads were spoiled, and many smooth places became rough.” (3 Ne. 8:13).

Helaman 7:10 is the only reference to a market in the entire text. This was the “chief market” in the city of Zarahemla. We infer there were other markets because this was the “chief” one, and because “there were many merchants in the land,” (3 Ne. 6:11), but of course even tribal societies have extensive trade networks, which requires some form of market and merchant. Chiefdoms would have more sophisticated trade systems.

_______________________________

Let’s get back to the basic premise of the article; i.e., that there is archaeological evidence of state-level society in Mesoamerica but no evidence of state-level society in North America.

This is really a question of expectations vs. reality.

If we accept what the Book of Mormon text says, we have a large population of tribal-level people (Lamanites throughout, people of Zarahemla for hundreds of years) contrasted with a small population (the Nephites) that achieves a chiefdom/state-level society for about 130 years (following Mosiah’s discovery of the people of Zarahemla).

The state-level society survives a devastating war to prosper for a few years before the government is overtaken by Gadianton robbers. Once the robbers are defeated, old cities were repaired and roads built. But soon the government collapses and the people divide into tribes. Then the destruction in 3 Nephi 8 occurs. “Many great and notable cities were sunk, and many were burned, and many were shaken till the buildings thereof had fallen to the earth… and there were some cities which remained, but the damage thereof was exceedingly great.”

Assuming there was evidence of state-level society that survived the wars and tribalism, what evidence would have survived this destruction? The scripture says the destruction was intended in part to hide the abominations of the people, which implies obliteration of the society, including its art and culture.

4 Nephi 1:7-8 explains that the Nephites rebuilt the burned cities (another indication that they used wood, not stone, for construction), but not the cities that were sunk. After a period of peace during which little is known about the form of government, the society returned to tribalism (verses 36-7). Wickedness prevailed, to the point that Ammaron hid up the sacred records.

Society continued to degenerate to the point that Mormon says “it was one complete revolution throughout all the face of the land.” (Mormon 2:8). Mormon was unable to describe “the horrible scene of the blood and carnage which was among the people.” Towns, villages and cities were again burned throughout the land. Implements of war are the only man-made objects mentioned in the text.

Throughout the text, from Enos until Mormon, the Lamanites sought to destroy the records. That’s why Mormon hid them in the hill Cumorah (Morm. 6:6).

Finally, of course, the tribal Lamanites prevailed. Nephite culture, to the extent it was state-level at all, was annihilated.

In summary, the Book of Mormon describes a minority population that achieved what could be deemed a state-level society for about 150 years that was characterized by intense warfare and conflict. Even after the wars, the Nephite society was destroyed three times; first by the Gadianton robbers, second by the destruction preceding Christ’s appearance, and third by the final wars with the Lamanites.

What aspects of this brief state-level society could be expected to endure these repeated devastations?

The cities, towns, and villages were burned by the Lamanites, who were determined to wipe out every aspect of Nephite culture possible, including writing. The one thing the Lamanites would be unable (in a practical sense) to destroy was earthworks. These don’t burn and they’re difficult to destroy.

And that’s what we find in North America.

The Book of Mormon does not describe an enduring state-level society. It explicitly rejects the idea of a preserved written history, in stone or otherwise. Archaeological evidence of an enduring state-level society would contradict the text.

Source: Book of Mormon Concensus